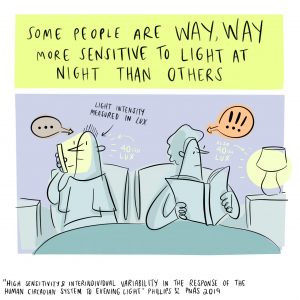

Humans evolved in an environment with only very bright (sun) or very dim (moon or fire) sources of light. Today, artificial lighting enables us to spend hours per day at intermediate light levels. Our recent study shows that the response of the circadian system (the ‘body clock’) to light across this intermediate range is hugely different between people.

These differences may help to explain individual differences in body clock timing, as well as how we adapt when our clock is challenged. The body clock controls the timing of many systems in our body, including our metabolism, sleep, and how alert we feel.

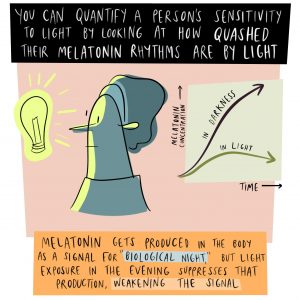

The timing of the body clock is set by when we are exposed to light. In humans, light exposure in the evening suppresses the production of melatonin (a sleep-related hormone) and delays the timing of the body clock, so that we feel sleepy later. Suppression of melatonin is controlled by the same brain pathway that communicates light input to the body clock, and can be used as a measure of light sensitivity.

If your melatonin is more suppressed by light, you are more sensitive to light. We know that some groups are unusually sensitive. For example, high light sensitivity has been associated with delayed sleep-wake phase disorder, a condition where individuals cannot get to sleep until very late.

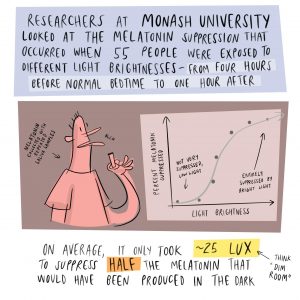

Our recent study, published in the scientific journal PNAS, studied inter-individual differences in light sensitivity [Phillips, Vidafar … Cain et al]. We investigated melatonin suppression in great detail by studying all of our participants at various light intensities.

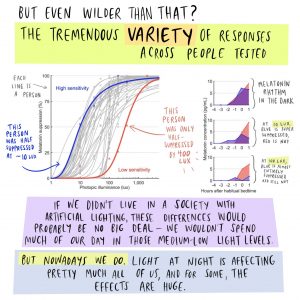

Although the people we studied were all healthy young adults, we found very large differences between them in light sensitivity – there was more than a 50-fold difference in the level of light needed to suppress melatonin to 50% of its natural level.

Although the people we studied were all healthy young adults, we found very large differences between them in light sensitivity – there was more than a 50-fold difference in the level of light needed to suppress melatonin to 50% of its natural level.

The most sensitive individual experienced over 50% suppression in very dim reading light, whereas the least sensitive individual required bright office-level light to achieve the same level of suppression. We also found that during the evening, around bedtime, humans are incredibly sensitive to even very low lighting.

At the group level, we found that melatonin was suppressed by over 50% in the lighting of about 30 lux – similar to light produced by a floor lamp, or a bright smartphone screen.

These large inter-individual differences may help to explain why some people are more vulnerable to sleep and mood problems than others. Individual levels of light sensitivity may also contribute to how well we adapt when we do shift-work, or when we travel across time-zones.

Our findings also suggest that the lighting most people have in their homes at night, leading up until bedtime, maybe having a very negative effect on the body clock. Given the large differences found between people, you might also want to consider that even if you don’t feel the impact of keeping the lights on until bedtime, others in your home might, and this could be impacting their body’s rhythms.

Our findings also suggest that the lighting most people have in their homes at night, leading up until bedtime, maybe having a very negative effect on the body clock. Given the large differences found between people, you might also want to consider that even if you don’t feel the impact of keeping the lights on until bedtime, others in your home might, and this could be impacting their body’s rhythms.

Elise McGlashan, PhD and Parisa Vidafar, PhD work as research fellows at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia. Twitter: @elisemcglashan

Image credit: Olivia Walch (Twitter: @OliviaWalch; website: www.oliviawalch.com)